The first thing that hits you is the density. Quiapo has its own gravity. The basilica rises like a fortress of devotion, its yellow façade soot-streaked and stubborn against the sky. Around it swirls a vortex of bodies, vendors, beggars, devotees, pickpockets, tourists, office workers with lanyards bouncing on their chests, mothers shoving baby bottles into the hands of older siblings. Jeepneys crawl by like armored beetles. Incense mingles with the smell of frying lumpia.

I came here again this year, with friends, one of them a foreigner eager to buy anting-anting. I thought I was only tagging along. Instead I found myself tracing the paths I’ve walked in this district across decades, like thin threads crisscrossing through time.

Quiapo has never been a destination to me so much as a stopover, a place I pass through at certain thresholds in my life.

Quiapo was where I bought my first pair of eyeglasses. , bright and narrow, a blur of glass cases and clicking tools, the optometrist balancing a metal trial frame on my nose while the city roared outside. Afterward I stepped out blinking at the sharpness of the world, the basilica suddenly crisp against the sky. Jeepneys crawled by in sharp blocks of red and chrome. Everything seemed hyperreal, as though I had been walking through fog my whole life and only then discovered the air had texture. That moment, seeing clearly again will always smell faintly of sweat, candle smoke, incecnse, and rubbing alcohol.

When I was in college, I got lost here trying to find Welmanson to buy beads for a business project. Everyone in school said if you wanted to make accessories to sell at bazaars, you had to go to Welmanson. It felt like a rite of passage, like a secret door into adulthood. I remember asking for directions from vendors who waved vaguely in conflicting directions, wandering down Hidalgo Street with its camera shops and pawnshops, until the street narrowed into a dim hallway stacked with glass beads, chains, clasps, sequins.

And years before that, right after high school, I worked my first job at the Jollibee in Isetann Recto. I can still feel the fryer oil mist on my skin, the heat of the kitchen, the secret thrill of stealing a fry when the supervisor’s back was turned. After closing at night, I would walk past the small and dingy motels, and then traversing down to Avenida and finally, up the Carriedo LRT before coming home, wondering if anyone else on that darkened ride also smelled of grease and exhaustion.

For a long time, Quiapo was just that for me, the place between things. A crossing. A blur.

The Basilica and the City That Formed Around It

But every time I come back, the basilica stands there like an anchor.

The Minor Basilica of the Black Nazarene, better known simply as Quiapo Church, was built and rebuilt on this ground since the 1580s. The current structure, with its pale yellow baroque façade and twin bell towers, was completed in the 1930s after earlier versions were destroyed by fires and earthquakes. Inside sits the Black Nazarene, a life-sized statue of Christ carved from mesquite wood in Mexico and brought to Manila in 1606. Legend says it darkened when its galleon caught fire during the voyage but survived unscathed, which is why it is considered miraculous.

Every January 9, the image is paraded through the streets during the Traslación, followed by millions of barefoot devotees. The crowd moves like a living sea, surging forward in waves, trying to touch the Nazarene’s robe or pull the rope of its carriage. It is one of the largest religious processions in the world. Many of the devotees return year after year, fulfilling vows made for healings, recoveries, reprieves. It is an event soaked in desperation and faith, equal parts chaos and devotion.

Even on ordinary days, the basilica feels alive in a way most churches don’t. Inside, there is always a hum of whispered petitions. Outside, devotion spills into the streets and reshapes itself.

Plaza Miranda: Faith With Teeth

Just outside the church gates is Plaza Miranda, which has seen its share of miracles and violence. There’s the 1971 bombing during a Liberal Party rally that left nine dead and was precursor to the Martial Law, decades before it became simply a noisy forecourt of candle sellers and vendors.

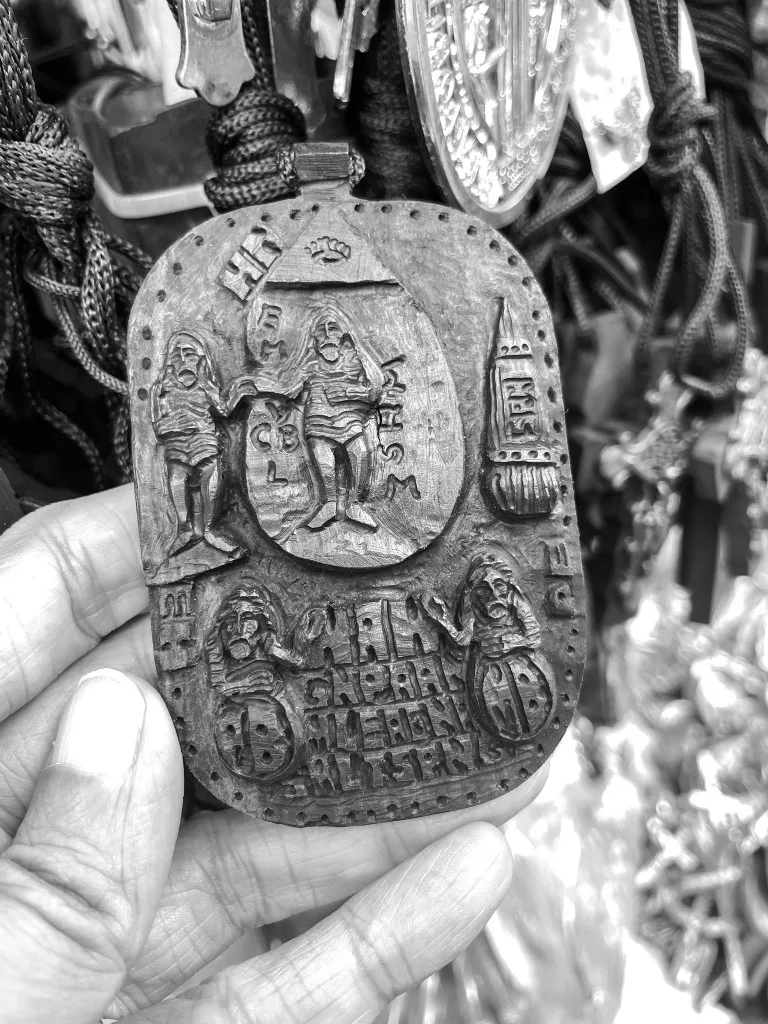

Here, Catholic iconography merges seamlessly with older protective magics. Tables sag under the weight of scapulars, rosaries, and saints’ statues. Beside them gleam the stalls of anting-anting sellers, each one a small archive of Filipino cosmology:

- Birhen Maria / Infinito Dios medallions or embroidered cloths, carried for divine protection.

- Pangkontra charms against kulam, usog, or aswang.

- Sator Squares, the ancient Latin palindromic grid believed to repel evil.

- Medalya de Oro, golden disks etched with saints and mystical sigils.

- Tres Personas medallions invoking the Holy Trinity.

- Sagrado Corazon, for courage.

- San Benito medals, once Catholic objects now layered with local exorcism prayers.

I watched a woman hum orasyon under her breath while carving an inscription onto brass. A man slipped a San Benito medal into his wallet as a venerated talisman. My understanding of these is born out of a sort of cultural amazement. My husband explains that in itself, these are merely things without meaning, and the owner is the one that breathes power onto the icon. One stall displayed bottles of pampalaglag tea beside pampakapit potions without a hint of irony. A woman by the corner advertises fortune telling. Faith here doesn’t separate itself from commerce. It takes whatever form it needs.

Commerce and Stopovers

Quiapo has always been a city of trades.

In the 19th century, Calle Hidalgo was known as “the most beautiful street in Manila,” lined with grand bahay na bato owned by the elite, with capiz windows, wrought-iron balconies, and wide azoteas that overlooked the Pasig. The American colonial period transformed it into a commercial district. Chinese-Filipino merchants opened shops, and the district grew into Manila’s primary marketplace. If you look hard enough, you can still see these architecture with the old shops hidden behind street shops.

Quinta Market, built in the 1850s beside the Pasig River, became the city’s central food hub. This was also near where the first imported shipments of ice from Boston were unloaded in the 1840s, blocks wrapped in sawdust, melting as they crossed the tropics. That arrival of ice changed the city’s palate, paving the way for chilled treats like halo-halo decades later. Coldness entered Manila here, reshaping how the tropics imagined refreshment.

Today, the old grandeur has frayed but not disappeared. R. Hidalgo remains lined with photography shops, a nod to the district’s long history as Manila’s photographic center. Vintage lenses, film rolls, tripods, and light meters stack up behind glass. The opticians of Villalobos crank out prescription glasses while you wait. Pawnshops glitter with thin gold chains. Bookstores spill out cheap secondhand textbooks onto the sidewalks.

And tucked inside this thrum are the eateries, tiny warrens of heat and broth.

Palabok and Breathing Space

At noon, we ducked into Resto Mondragon, a local legend that has quietly gone viral online for its cheap meals. Inside was a blur of clattering plates, sweating ceiling fans, and bowls of sotanghon, palabok, sinigang na ulo ng isda, and buto-buto big enough to anchor the table. The broth was rich and sticky on the lips. The meat surrendered to the spoon. Around us, families hunched over red bowls, workers in damp uniforms scrolled their phones, a group of students debated the best route to the LRT.

Mondragon felt like another stopover, the city’s chaos briefly held at bay by broth. And then we stepped back outside and it swallowed us again.

A Turn Toward the Hidden Markets

Instead of turning straight down Hidalgo, we veered toward the side streets behind the basilica where the Muslim market begins. The air shifted there, less incense, more grilled kebab smoke and turmeric and clove. Stalls brimmed with halal meats, dates in crinkled boxes, bolts of shimmering fabric, stacks of batik sarongs. Women in niqabs bargained over fresh paria and sakurab, men stirred giant pots of pastil rice wrapped in banana leaves. It felt like slipping through a fold in the city, another Manila running parallel to the one I thought I knew.

Under the Quezon Bridge, the noise softened into the wooden clatter of the Ilalim ng Tulay crafts market. This is Manila’s largest native crafts bazaar, and it smells of rattan and varnish. Stalls overflow with woven baskets, buri hats, carved wooden spoons, baybayin-inscribed keychains, brass bangles from Mindanao, abaca slippers, giant wooden spoons and forks, the full vocabulary of every Filipino living room from the ’80s onward. Tourists come here for souvenirs. I stood there mostly stunned that all these regional traditions had survived here under the traffic, each object shaped by someone’s patient hands then sold for the price of a fast-food meal.

The House I Still Haven’t Entered

Most walking tours loop from the basilica to Plaza Miranda, swing down Hidalgo’s camera row, then pause at the Bahay Nakpil-Bautista, a 1914 bahay na bato turned museum that once housed revolutionary heroes like Julio Nakpil and Gregoria de Jesús, widow of Andrés Bonifacio. It has been on my list for years, yet somehow I’ve never crossed its threshold.

I passed its façade once, capiz windows glowing, wooden balusters carved like lace, but kept walking, pressed for time. That house still waits for me, and I promise myself I’ll step inside on my next return, and maybe trace a line through the other crumbling mansions along Hidalgo before they vanish behind tarpaulins for good.

Plaza Miranda Again, and What Heritage Means

We ended at the Plaza Miranda marker, that small granite obelisk declaring the square’s history. It seemed absurdly small for the weight it carries: bombings, rallies, revolts, speeches, worship, commerce. The plaza has been Manila’s public stage for centuries.

In 2018, the National Historical Commission declared Quiapo a Cultural Heritage Zone under the National Cultural Heritage Act (RA 10066). On paper, this gives the district formal protection, heritage guidelines, conservation funding, oversight. In practice, it recognizes something harder to contain, this swirl of faith, folklore, and trade that refuses to stand still.

Heritage here is not quiet. It won’t stay on plaques. It moves through the press of shoulders, in the clatter of lunch at Mondragon, in the way people arrive, reinvent themselves, and move on.

The Personal Map Underneath

When I think about it now, Quiapo has been part of my life in fragments:

- My first eyeglasses on Villalobos.

- My first job at Jollibee in Isetann, skin raw from fryer grease.

- My first small business attempt, lost and sweating while searching for Welmanson beads.

- This recent day, standing in front of the basilica with an amulet in my pocket and the broth of bulalo still warm in my chest.

These fragments form their own map beneath the official one. A private cartography of thresholds and crossings.

That might be why Quiapo feels inexhaustible. It isn’t only its history that draws people. It’s how it absorbs everyone who passes through, students, workers, hustlers, believers, and makes them part of its living archive.

Every time I return, the basilica waits like an anchor. Around it the streets shift, stalls change, old houses collapse and are reborn as cellphone shops, but the pulse stays the same. Quiapo is Manila stripped down to its rawest instinct, to endure by changing, to preserve by becoming.

Update: This essay was later published on Rappler.

✧ Walking Map: A Ramble Through Quiapo

Start: Villalobos Street

Begin where the opticians cluster shoulder to shoulder, their signs stacked like book spines. This is where I bought my first glasses, blinking at the world as it snapped into focus. Today, you can still get a full eye exam and prescription glasses in under an hour, the same clatter of lens grinders in the background.

Quiapo Church / Minor Basilica of the Black Nazarene

Step into the basilica courtyard, where incense clings to your hair and the hum of whispered petitions fills the air. Inside, the Black Nazarene glows under low light, dark and gleaming from centuries of touch. Pause here, if only to feel how the ground seems to vibrate with everything it has survived.

Plaza Miranda

Outside the gates, the plaza buzzes like an electrical current. Fortune tellers mutter orasyon behind cards, vendors hawk scapulars beside anting-anting: Birhen Maria, Sator Squares, Pangkontra, Tres Personas. This is belief turned into merchandise, into portable power.

R. Hidalgo Street

Slip down Hidalgo, once called the most beautiful street in Manila. Peer into its camera shops stacked with vintage lenses and film rolls, echoes of its 20th-century life as the city’s photography capital. A few crumbling bahay na bato still stand here, their capiz windows half-hidden behind tarpaulins and tangled wires.

Quinta Market

Cross over to the market by the river. The air thickens with steam and shouts. This was once the city’s central market, and nearby the first blocks of Boston ice were unloaded in the 1840s, coldness arriving in the tropics. It’s easy to imagine the shock of it while holding a halo-halo in your hand.

Resto Mondragon

End here, where the broth is rich and the tables are crowded with strangers sharing silence. I sat here once, after hours of wandering, and the chaos outside went soft. You’ll need that pause before stepping back into the city’s current.